‘Our Doors Would Have to Close’: Trump’s Proposed Cuts Threaten Tribal Colleges

Tribal college leaders said the proposed funding cuts violate treaty responsibilities and would devastate tribal communities while harming Montana’s economy

By Nora Mabie, Montana Free Press

After losing her mother, sister and brother to diabetes, Joilynn Loves Him decided to study health at Northwest Indian College, a tribal college in Washington.

Her experience at the school “has been life-changing.”

“The teachers make sure we’re successful,” Loves Him said. “They’re really there for students, and they understand that life happens. If I were at a normal Western college, I’m pretty sure I never would’ve made it.”

Such sentiments about tribal colleges are common among students. Tribal colleges and universities are institutions of higher education, chartered by tribes, that aim to meet the educational and cultural needs of Native communities. The schools, open to all, operate on slim budgets and offer a variety of degrees, host community events and advance cultural and language revitalization efforts. Tribal colleges provide more than just education — they serve as a resource hub in rural communities and act as an economic driver.

But looming federal cuts have thrown their future into limbo.

Reducing government spending is among President Donald Trump’s top priorities, and his administration recently proposed drastic cuts to tribal colleges and universities, reducing federal operational funds for the schools by about 90%. The proposal, included in a June 2 budget request from the Department of the Interior to Congress, reduced funding for postsecondary institutions from more than $182 million to just over $22 million, an amount tribal college leaders say would likely lead to the closure of their institutions.

Loves Him, who grew up on the Fort Peck Reservation, is set to graduate with her associate’s degree this fall and hopes to enroll in the school’s bachelor’s program focused on community behavioral health. She dreams of providing quality, culturally informed health care in tribal communities, the type of care she said her family members didn’t have access to.

Now, like tens of thousands of tribal college students nationwide, Loves Him, 50, fears her school may have to close its doors.

“I’ve worked so hard,” she said. “ … I’m worried I won’t be able to finish my bachelor’s degree.”

Montana is the only state in the country with a tribal college on every reservation. School leaders told Montana Free Press the proposed funding cuts violate treaty responsibilities. They would also devastate tribal communities and harm the state’s economy, leaders said.

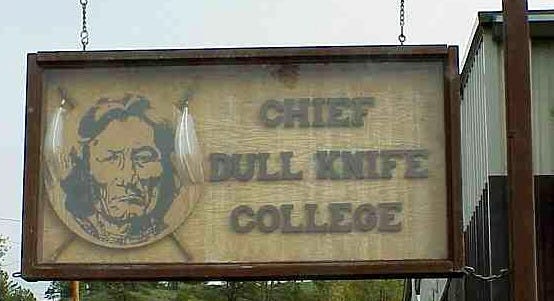

“Our doors would have to close,” said Eva Flying, president of Chief Dull Knife College on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in rural southeastern Montana. “…Jobs will be lost. Programs will have to close.”

TRIBAL COLLEGE FUNDING

While some states, including Montana, provide funding to support non-Native students at tribal colleges, the schools receive the vast majority of their funding from the federal government. That’s in part because the U.S. government has a treaty obligation to tribes to provide education.

Ahniwake Rose, president of the American Indian Higher Education Consortium, likened the main federal funding streams for tribal colleges to a three-legged stool. Tribal colleges receive money from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Department of Education and the Department of the Interior. Money from the USDA and Department of Education is “flat funded,” meaning it does not increase year to year, so funds from Interior, Rose explained, account for the majority of tribal college funding.

“It was a surprise to see the huge proposed cuts coming out of the Department of Interior for our tribal colleges,” she told MTFP on June 25. “If you take one of those legs away, it collapses.”

While Congress must approve the proposed cuts, Rose said that if they were to take effect, “there is no way that [tribal colleges and universities] could survive.”

Unlike some postsecondary institutions, most tribal colleges do not have large endowments. And critical to the schools’ mission is keeping tuition low, so that education remains accessible to people who otherwise might not be able to afford it.

“This type of drastic federal funding cut would immediately impact the way that [tribal colleges] are able to operate,” she said.

STUDENTS AND STAFF

Congressional leaders have begun the appropriations process by which lawmakers dedicate funds to federal agencies and programs. While the Trump administration’s proposal has not yet been approved, tribal college leaders say the threat of closure has already impacted students and staff.

“For our faculty and staff, it’s not fair to them to live in this uncertainty,” said Blackfeet Community College President Brad Hall. “It trickles down, the anxieties, the stress. The fears trickle down and there will come a time when it has a direct impact on our students.”

Some students say they’ve already felt the effects of the proposed cuts.

Shanell Lavallie, 26, recently graduated with a master’s degree in education from Salish Kootenai College on the Flathead Reservation. Her research focused on effective strategies to teach reading, skills she plans to apply at Great Falls Public Schools, where she teaches third grade.

Reflecting on her experience at Salish Kootenai College, Lavallie said she needed the school “more than I realized.”

“Tribal colleges are founded on community and culture,” she told MTFP. “The teachers really prioritize knowing who you are as a person. It’s hard to explain, but when you have relationships with teachers and you really feel like they see you, it helps you excel.”

Antone Manning, who grew up on the Fort Peck Reservation, started taking classes at Haskell Indian Nations University in Kansas in January. He had previously studied at Montana State University Billings but said the school wasn’t the right fit.

“You kind of feel like you’re the biggest minority,” he said.

His first month of school at Haskell, Manning said, immediately felt different. The tribal university serves about 1,000 students from tribes nationwide. Manning felt like he was part of a rich community. He could tell Haskell was a place he’d make lifelong friends.

A month after Manning enrolled, about 30 Haskell employees, or about a quarter of the school’s staff, lost their jobs when the Trump administration, at the direction of the Department of Government Efficiency, implemented mass federal workforce reductions. While some staff have since been reinstated, in March three tribes filed a lawsuit in federal court alleging the firings violated the federal government’s treaty obligations.

Manning, 21, watched as professors lost their jobs. His friends’ classes were canceled. The school, he said, started serving two meals a day instead of three. Toilet paper ran low.

“It was rough,” he told MTFP, adding that things have gotten a little better in recent weeks.

But when Manning recently signed up for a class required for his degree in health sports and exercise science, he was informed the class had been canceled because not enough students had registered.

“A lot of kids don’t want to come to a college if it’s going to get shut down,” he said.

Manning has dreamed of becoming a physical therapist ever since he broke his wrist in the sixth grade. He’d planned to enroll in Haskell’s exchange program with Kansas University to pursue a bachelor’s degree. Now, he feels like that future is uncertain.

“I don’t even know,” he said. “It sounds like we’re not going to be a university no more.”

TRIBAL COLLEGE PRESIDENTS SOUND THE ALARM

If tribal colleges were to shutter, school leaders said, communities would lose access to critical education and training opportunities, as well as events, workshops, programs and cultural connections. School closures, they noted, would also devastate local economies.

Most tribal colleges in Montana are located in rural areas, and they’re often among the largest employers in their communities. Blackfeet Community College employs more than 100 people on the reservation. Fort Peck Community College has 70 full-time employees, and Aaniiih Nakoda College on the Fort Belknap Reservation has 50. School closures, tribal leaders say, will result in a significant reduction in local workforces.

Rose, the American Indian Higher Education Consortium president, said federal funding cuts would trigger “a deep source of economic strain on the community.”

“You’re looking at job removal,” she said. “You’re looking at tax revenue that’s going to immediately slide down as folks aren’t able to contribute to the economy.”

Sean Chandler, president of Aaniiih Nakoda College, said the cuts would also inhibit the development of a future workforce.

“We no longer would be able to build capacity for our reservation,” he told MTFP in a recent interview. “We are producing some great students, some great citizens of our nations. We are producing educators and nurses — not just on our reservation, but people who serve other communities along the Hi-Line all around us.”

A recent study conducted by a labor market analytics company for the American Indian Higher Education Consortium revealed that from 2022 to 2023, Aaniiih Nakoda College added about $12.2 million in income to the Blaine County economy in north-central Montana. The same report estimated that about 1 in every 14 jobs in Blaine County is supported by the activities of the tribal college and its students.

“The college benefits local businesses by increasing consumer spending in the county and supplying a steady flow of qualified, trained workers to the workforce,” the report reads.

WHERE DO MONTANA LAWMAKERS STAND?

Tribal college leaders in Montana say they have urged the state’s congressional leaders, all Republicans, to oppose the suggested cuts.

Senator Steve Daines sits on the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, a group of lawmakers who study tribal issues and propose legislative solutions. Asked whether he supports the cuts to tribal colleges, a spokesperson said Daines “supports Montana’s tribal colleges and is taking a close look at proposed changes to funding.”

Asked the same question, Representative Troy Downing said he “will continue to be a champion for [tribal education] institutions as Congress considers additional funding measures and welcome the continued input of my constituents.”

A spokesperson for Representative Ryan Zinke said the congressman “is reviewing the president’s proposed budget and working through the appropriations process to craft funding bills that will benefit Montana, the tribal nations and America.”

Senator Tim Sheehy’s office did not respond to two emailed requests for comment on June 23 and 25.

Chandler said that as the stress of looming cuts weighs on him and his colleagues at Aaniiih Nakoda College, he can’t help but think of his ancestors, who faced similar challenges at the hands of the federal government. He thinks of the time when European settlers and the U.S. Army massacred buffalo, driving tribes to starvation. Or when Native children were taken from their homes and forced to attend culturally oppressive boarding schools.

“I know they didn’t get through their challenges easy,” Chandler said. “But the point is, they made it through. They survived. They coped, strategized and thought about their future people.”