The Toll of Bozeman’s Housing Crisis

At the small city’s only emergency shelter, demand is higher and the work is harder than ever

By Nick Bowlin, High Country News with photos by Will Warasila

Last year, a mass of Arctic air sent temperatures in Bozeman, Montana, plummeting to minus 30 degrees Fahrenheit — temperatures at which exposed skin can develop frostbite in less than half an hour. Massive snowstorms might be welcomed by Montana’s recreational skiers, but for people sleeping outdoors, cold weather can kill. And for years, Bozeman’s unhoused population has ballooned alongside its housing prices, with campers and RVs congregating along undeveloped streets on the city’s fringes. Surrounded by mountains and located near famous ski resorts and the Yellowstone area, the city has rapidly become one of the region’s most expensive places.

This article originally appeared in High Country News.

As the temperature dropped, staff at the Warming Center, Bozeman’s only year-round homeless shelter, sprang into action. Members of the street outreach team fanned out, warning people sleeping outdoors of the impending cold, urging them to get inside and passing out blankets and food. The shelter is operated by the nonprofit Human Resource Development Council (HRDC), which also runs a smaller shelter in nearby Livingston and provides food, housing and financial assistance throughout southwestern Montana. The shelter’s leadership decided that the Warming Center would remain open all hours rather than closing for its regular midday cleaning. Volunteers were called in to staff the front desk and help guests. One night, when the shelter was just two occupants shy of the fire marshal’s occupancy limit — 120 people — the staff feared they’d have to turn people away.

A U.S. Government Accountability Office study estimated that a $100 increase to the median rent was associated with a 9% increase in the rate of homelessness.

Located on the edge of Bozeman, away from the swank city center, just off I-90 near cheap motels and big-box stores, the shelter, a one-time roller rink, is cavernous and echoey. The space is split between men and women, with a set of bunks for those who have special medical needs or require extra supervision. For five days, while temperatures remained dangerously low, the space, which normally feels expansive, was packed, and the crowding, the constant proximity, wore on both staff and visitors. Arguments, mental health episodes and drug and alcohol-related problems increased. But even before the cold snap hit, staff had been dealing with uncommon and disturbing behavior patterns.

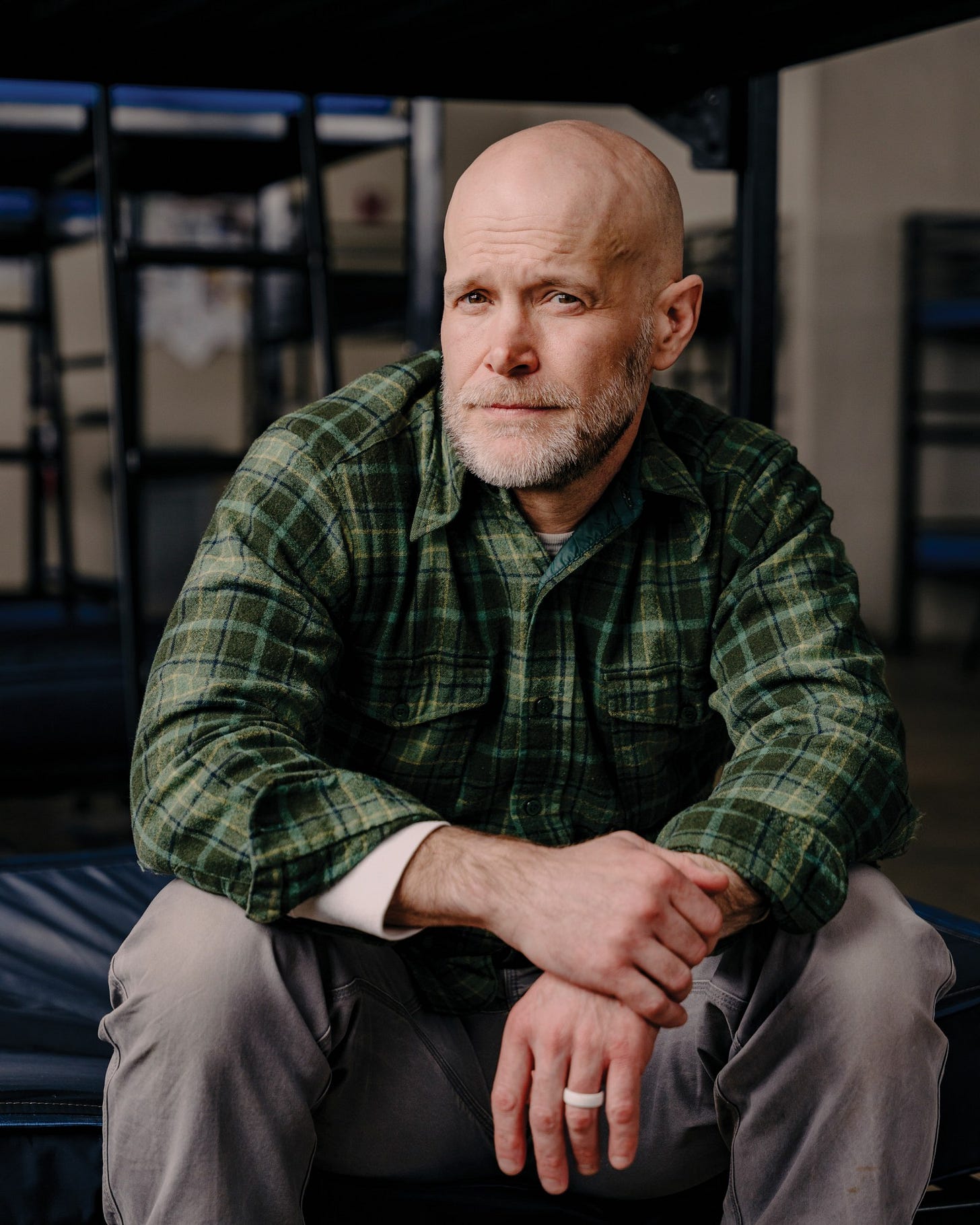

For Brian Guyer, HRDC’s housing director, the reasons were clear. A local mental health center, which included a crisis unit, had closed. More recently, Gallatin County’s alcohol and drug service program shuttered as well. Budget and staffing issues contributed to both closures. And compared to other states, Montana was hit especially hard when the federal government rescinded its COVID-era Medicaid expansion. Guyer, who is in his 40s, with a shaved head and square-toed boots, exudes a noticeable air of calm despite the growing unpredictability of his job and the unprecedented demand for services.

“We’re not mental health specialists,” he said. “We’re not behavioral health providers. We’re not medical care providers.”

“All of these things sort of come to a head at the shelter. We see the culmination of a mental health crisis, housing crisis, a wage crisis, a drug crisis.”

The Bozeman location is meant to be an emergency shelter. Other local organizations provide housing for families and domestic violence survivors, but HRDC’s shelter is the sole place where someone without a place to sleep can walk in and get a bed.

In recent years, however, HRDC’s employees have taken on roles beyond their training and capacity. As Bozeman’s unhoused population has increased dramatically — up 280% between 2018 and 2024, according to an annual survey — HRDC has tried gamely to keep pace, expanding its services from seasonal to year-round and providing more space at a new location. But the need has outstripped its ability to provide. And for people sleeping outdoors, HRDC’s warming shelter is often the only place to turn, the last still-hanging strand in Bozeman’s tattered safety net.

“All of these things sort of come to a head at the shelter,” Guyer said. “We see the culmination of a mental health crisis, housing crisis, a wage crisis, a drug crisis.”

THE WINTER was challenging even before the severe cold hit. At 2:20 a.m. on Christmas Day, a young man was found lying on the bathroom floor, unresponsive. When staff reached him, his face was blue. Suspecting a fentanyl overdose, they gave him two doses of Narcan, a nasal spray designed to reverse opioid overdoses. Emergency services arrived shortly after and administered CPR, but to no effect. Half an hour later, the man, who was only 23, was pronounced dead at the scene.

In February, another man fatally overdosed in his car; he’d been in and out of the shelter and was well-known in that community. His infant twin sons had been staying with their mother at a transitional housing facility also run by HRDC. That same month, a third person died of an overdose at an HRDC site. Shelter staff, overworked and burned out after the cold snap, tried to contain the fallout, checking in with the deceased’s friends and with shelter guests who were struggling with addiction.

“You’re talking about well over 100 people that have co-occurring traumas, they’re dealing with that loss at the same time,” Greg Overman, HRDC’s supportive housing manager, said. “And what we’re trying to prevent is the domino effect.”

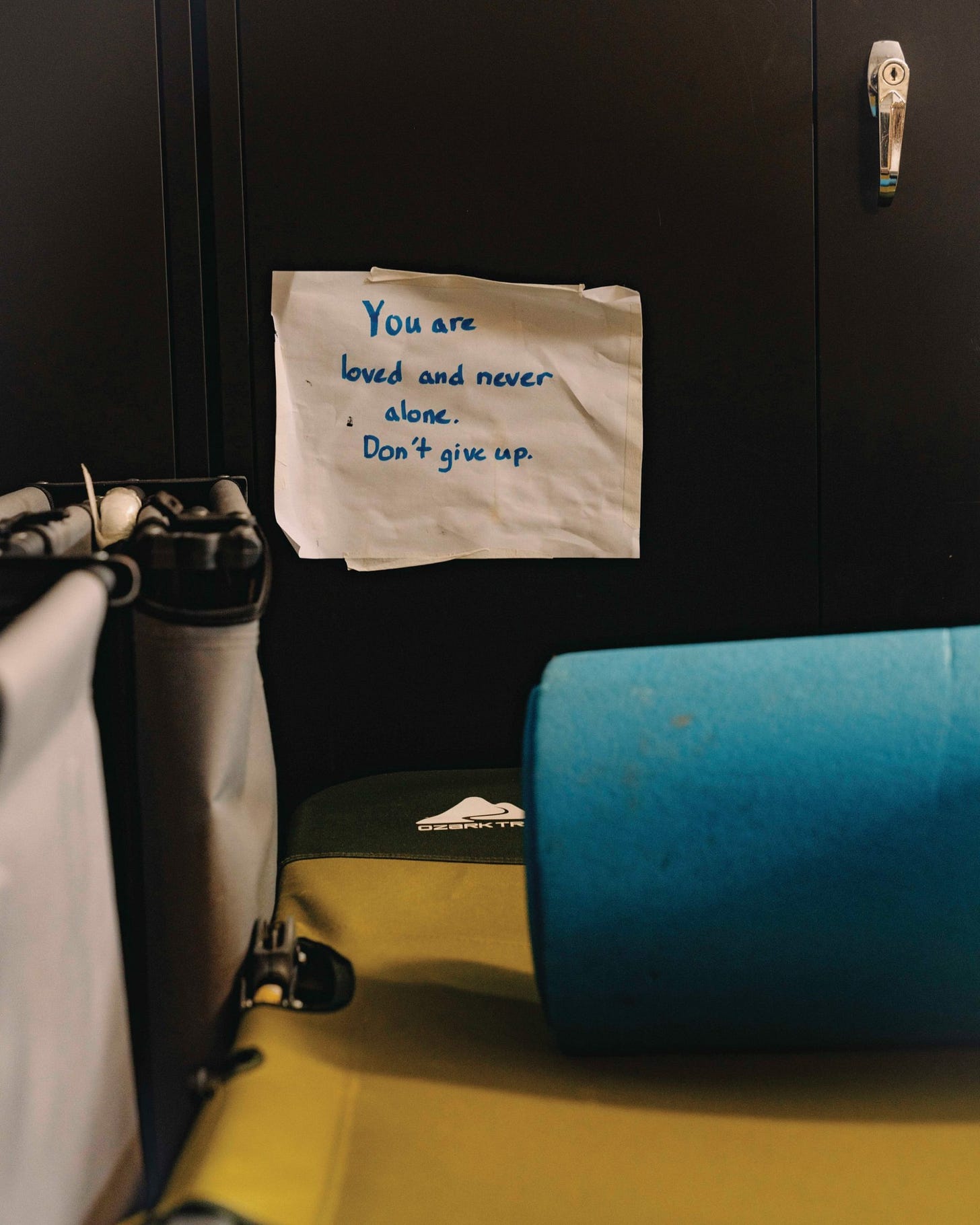

But the tragedies continued. In late February, a man who was relatively new to both the shelter and the staff walked outside to a tree near the shelter’s front gate, looped a rope around a branch and hanged himself. Mychal Anne Marsolek, the overnight operations lead, was on duty that night. Another worker saw the man hanging from the tree on a security camera feed, and shelter employees rushed outside. Marsolek called 911 while her co-workers took him down, removed the noose and gave him CPR. Eventually, he regained a pulse and was taken to the hospital.

Days after the incident, the man returned, walking in quietly through the shelter’s front doors. He was greeted by the same people who, days earlier, had taken him down from the tree. He had sneaked out of the hospital.

“We were just stunned,” Guyer said. “It was like seeing a ghost.”

Marsolek began volunteering at the shelter a few years ago. She found that she loved the work, and, as she put it, was “not able to stay away.” She eventually applied for a full-time job. Months after the suicide attempt, sitting in the empty shelter, Marsolek, wearing a denim jacket and chunky glasses, said that the memories of that night continued to haunt her. “This was absolutely one of the most intense situations that I have been a part of,” she said.

THE GAPING ABSENCE of services for Bozeman’s poorest and most vulnerable has grown increasingly obvious in recent years, as the city has become a magnet for wealthy people and luxury real estate investment. In the last decade, Bozeman, population 57,300, has been among the nation’s fastest-growing small cities, attracting well-to-do people willing to pay for easy access to nearby mountain ranges and ski resorts. In early 2024, the median home price approached $1 million in the greater Bozeman area. A 2020 study from the U.S. Government Accountability Office estimated that a $100 increase to the median rent was associated with a 9% increase in the rate of homelessness.

From 2007 to 2023, the number of people experiencing homelessness in Montana increased by 89%, according to the Department of Housing and Urban Development. (Montana also had the nation’s highest suicide rate from 2021-2023.) These statistics and the shelter’s own demographic research refute an accusation that Guyer often sees online or hears: that, by its very existence, the shelter incentivizes unhoused people to come to Bozeman. According to HRDC, the vast majority of its shelter guests have been in Bozeman for over a year, and half have lived in the area for more than five years.

“Our data shows that the guests at the shelter are longtime Montana residents, and they’ve simply been priced out of homes,” he told me.

This myth, though, is pervasive in Bozeman, and it appeared prominently in the Facebook comments of a Bozeman Daily Chronicle story about HRDC in May 2024.

“If you build it, they will come,” wrote one commenter. “And come, and come.”

Dozens of comments expressed similar sentiments: “Build a nice homeless shelter. Guess what you get? Permanent homeless people.” “It is time to get the HRDC out of our valley.”

At times, this hostility leaves the digital sphere and enters everyday life. Crystal Baker, who runs HRDC’s Street Outreach Program, regularly visits people living on Bozeman’s streets with her team, offering aid and services. Once, she and a member of a local health clinic were checking on a man in a trailer when a woman drove up, rolled down her window and began yelling.

“She hung out the window and was banshee-screaming at all of us to get a job, that we were a waste of space, that we should just kill ourselves,” Baker said.

More recently, the desire to remove unhoused people has taken on the force of policy. In the wake of last year’s Grants Pass Supreme Court decision, Bozeman’s City Commission enacted a ban on sleeping on public property and created a temporary permitting system for people sleeping in streetside vehicles or campers, which will end on November 1. Violators can be fined up to $500 or face jail time. In Montana — including Missoula and Helena — and across the West, many municipalities are passing similar restrictions. Nationally, around 150 cities have passed or strengthened anti-camping rules, with dozens more pending, according to Stateline. And several other cold-weather cities in the Rocky Mountain West — including Park City, Utah, and Boise, Idaho — have, like Bozeman, only one year-round homeless shelter.

The Trump administration’s budget cuts have further complicated things: HRDC relies almost entirely on federal funding for rent aid, veterans’ assistance and family-specific programs.

“If you build it, they will come. And come, and come.”

“There are about 670 low-income individuals, families, pregnant women, people with disabilities and seniors across our service area who are receiving project and tenant based rental assistance,” Guyer wrote in an email. “Losing those resources could effectively double the number of unhoused people in our community.”

And funding emergency housing here presents its own set of problems. Guyer noted that federal funding supports more than half of HRDC’s public transit services. The Warming Center itself receives minimal federal help, less than 5% of its overall budget. But the shelter depends overwhelmingly on private funders and small donations, and the growing backlash against Bozeman’s unhoused people and those who aid them has made fundraising increasingly difficult during a time of tremendous need.

“Going out and talking about the need to put a roof over our neighbor’s head used to be a pretty easy sell,” he said. “That environment has shifted.”

LIKE MANY PEOPLE who use the shelter’s services, Cindy was managing on the surface but living one crisis away from financial ruin. (Cindy asked that we use only her first name.) Now in her 40s, she came to Montana from Ohio in the early 2000s to work at Yellowstone National Park as a hotel manager. She liked it so much that she encouraged a nephew and her mother to join her. A decade later, she moved to Bozeman, where she worked as a 911 dispatcher. Housing costs weren’t an issue at first, she recalled. Then, in 2017, Cindy suffered an injury at work, leaving her with chronic shoulder and neck pain. Unable to work as a dispatcher, she tried a desk job with the city, then a gate agent position at the airport, only to realize she couldn’t carry luggage. For a few years, she and one of her nephews split an affordable apartment.

“We were riding the line, but we were OK,” Cindy said — OK until 2023, when her nephew contracted COVID and developed a lung infection, causing him to miss work. Late rent fees piled up, and they were forced to leave the apartment last March. They spent a month in cheap motels before their savings ran out. Then, early one morning, Cindy recalled, they checked out of a room at a Super 8 and made their way to HRDC’s shelter, where they waited outside with all their belongings until the doors opened at 7 p.m. “It was really intimidating,” she said.

After their time in the motel, Cindy and her nephew spent every night at the shelter. During the day, she would often go to a local library, but in summertime, she would sometimes set up a tent in a permanent encampment for unhoused people not far from the shelter. She and her nephew are trying to save money for an overdue surgery; Cindy has a cyst that presses against her spine.

“There’s no more human experience than being alongside someone in the depth of their troubles.”

“I was working on getting (the surgeries) scheduled as we were being evicted, but now that I’m out here, there’s just too much,” she said. “I can’t get it started.”

During the day, Cindy’s nephew would leave the shelter and head for a shift at the nearby Walmart; many shelter regulars work low-paying jobs in Bozeman’s massive service and tourism industry. This became clear one evening in late May, when I observed HRDC’s staff doing evening intake. Many of the people who pushed through the doors had just come from work, wearing chain-store uniforms or boots caked in construction-site dirt. One man in a hoodie stamped with a contractor’s logo said that he’d been working on a building in the Yellowstone Club, a hyper-exclusive private ski resort 45 miles south in Big Sky. He’d spent the day installing 400-pound wooden ceiling beams, only to return to Bozeman and a bunk in the shelter’s crowded men’s quarters.

“In a very perverse way, this is what the service industry workforce housing looks like,” Guyer told me.

The next day, I returned to the shelter around the time that an older woman shuffled out of a sheriff’s vehicle at the front entrance, wearing pink slippers and clutching several overstuffed duffel bags. Guyer and shelter staff spoke with her for several minutes before taking the bags to a storage closet. He returned to his cubicle, shaking his head. The woman had been working a hospitality job in West Yellowstone, on the other side of Big Sky, but was fired after she couldn’t handle the job’s physical demands. The loss of her job meant the loss of her employer-provided housing.

Versions of this scene are becoming increasingly common: older people who come to the shelter as a last resort. But the shelter isn’t set up to serve every visitor. “We can’t care for people who can’t shower themselves or are incontinent,” Guyer said. “But the hospital often won’t take them. We’re tolerating more than we should, if the other option is outside.”

FOR HRDC STAFF, the day-to-day job is full of moments like these — determining how to help people whose needs exceed what they can provide. On most days, the shelter takes in dozens of people, often more than 100. Staff members try to accommodate bunk requests and field complaints — accusations of stolen propane or missing charging cords. Sometimes they break up fights.

But the growing pressure plays out in ways that are sometimes shocking, even dangerous. In late June, early one evening, the phone rang. If the shelter wasn’t empty in the next two hours, the caller said, he would “light it up.”

Staff immediately began evacuating the building, with 90 or so people inside, hurriedly handing out food, sleeping bags, tents — anything they could to help people get through an unexpected night outdoors. Guyer was checking the shelter’s perimeter when he encountered a man he knew who often stayed there, sitting under a pavilion drinking a can of Mike’s Hard Lemonade. Several backpacks lay nearby.

Guyer told the man that, due to the threat, he needed to leave, and asked that he pour out his drink. The man complied and left with the backpacks.

That same man was ultimately arrested for the threatening call: Police found him carrying “a Glock 22 .40 caliber pistol, six extended magazines, a drum magazine, a 15-round magazine and 243 rounds of ammunition,” according to the Bozeman Daily Chronicle.

According to court documents, the man believed that unhoused people in Bozeman were being targeted for sex-trafficking and blamed the shelter.

“He was in the midst of a mental health crisis,” Guyer said. “I can’t help but think, had the safety nets that used to exist been there, maybe they pick up on this before it becomes this extreme.”

Nor are shelter staff immune from the forces that make housing in Bozeman inaccessible to all but the lucky and the wealthy. Guyer and his family had to leave for the nearby town of Livingston a few years ago when his landlord asked for a $1,600 rent increase. Marsolek, who works a second job at a local domestic violence aid organization, has dealt with a 30-day eviction notice and substantial rent hikes in Bozeman’s tight rental market, which has had a slim vacancy rate for years. Overman lives in a small town half an hour away.

HRDC staff acknowledge the difficulties, but they still insist they are fortunate to do this work — it’s a “privilege,” Overman told me, unpacking hot dogs and hamburgers at a picnic table in June.

“There’s no more human experience than being alongside someone in the depth of their troubles.”

“We can’t care for people who can’t shower themselves or are incontinent. We’re tolerating more than we should, if the other option is outside.”

Overman, who is tall and angular and wears a thick beard, witnesses such troubles but also sees slivers of hope in his work with chronically homeless people, those who have lived on the streets for years, sometimes decades. Many are unable to hold jobs. Others have long histories of encounters with law enforcement or profound addiction and mental health challenges.

Led by Overman, HRDC has tried to address this demographic with its Housing First Village project, which opened in November 2021. Between the emergency shelter and the highway sits a collection of 19 tightly packed tiny homes, brightly painted and arrayed around a grassy common area. Known simply as the Village, the project operates on a “housing first” model: Once people have a safe, stable place to live, the thinking goes, good things will follow. HRDC’s own data bears it out, Overman said.

“If you look at everybody that has lived at Housing First Village and the amount of time they’ve lived here, and then compare that equal amount of time to before they were in housing, what you see is that there’s around a 40% decrease in emergency room use,” he said. “There’s over a 45% decrease of bookings in Gallatin County Detention Center, over an 80% increase of preventative health access … and over a 50% increase in behavioral health access.”

A small party coalesced around Overman as he prepared the grill and hauled out plastic-wrapped cases of soda and water. Residents from the Village arrived slowly, as did a few shelter regulars and people from the encampments. HRDC caseworkers came and went, and two dogs tussled on the lawn. Overman talked about the country singer Morgan Wallen with a man holding a bottle of vodka. At one point, a Village resident arrived in a car, and the crowd clapped and cheered: She had recently regained custody of her infant daughter, who slept peacefully in her arms despite the noise.

Brittany, a young woman who lives in the Village, stood near the table. Since moving into permanent housing, she rarely interacts with police, who, she said, “lurk around and harass people” who live on the streets. And it’s been easier for her to avoid people who encouraged her drug addiction.

“I don’t have to go nowhere,” she said. “I have power, and I have running water, and I have a door that locks.”

I also spoke to James, who lived outside for years before finding housing at the Village. He wore a green hoodie and had a bandage on his hand. For months after he moved in, sleeping indoors felt strange, he told me, so he slept on the lawn.

“Never had a house of my own,” he said. “This guy gave it to me,” gesturing to Overman.

“I didn’t give it to you, you deserve it,” Overman replied. In general, Overman speaks quietly, but his reserved demeanor dissolved around the Village’ residents. He became voluble, telling jokes and animating the gathering.

“The things that seem to drive others away seem to strengthen their resolve.”

Six months later, that festive atmosphere was long gone; Bozeman was again frozen, dark and cold. In January 2025, the temperature dropped precipitously, and the shelter remained open all day. Valentine’s Day brought another cold snap, and for several days staff members were once again constantly on-duty. More than 100 people filled the beds each day. A few smuggled in alcohol, and staff suspected that someone was getting high in the bathroom. There were disputes, outbursts and a mental health breakdown. Cleaning was challenging, and by the end, the place reeked of packed-in bodies.

“It’s sad to just watch people unravel because they don’t have the space that they need,” Guyer said, the day after the cold ended and the shelter resumed its normal schedule. It was a difficult few days, but a success, he said: HRDC reached unhoused people at acute risk of dying from exposure, and Guyer said there had been no reported fatalities when the temperature was regularly below zero. And staff diffused the potentially explosive moments.

The relative peace they maintained spoke to HRDC’s increasingly practiced and capable employees, Guyer went on, a testament to their training and the calm that comes from hard-won experience — from showing up no matter what, for the intense periods of extreme cold as well as for the pleasant springtime barbecues. It reminded me of something Guyer said months before, reflecting on his co-workers: “The things that seem to drive others away seem to strengthen their resolve.”

Will Warasila is a photographer focused on long-term documentary projects concerning the environment, particularly the slow violence wrought by corporate and political structures. Gnomic Books published his first monograph, Quicker than Coal Ash, in 2022.

Nick Bowlin is a contributing editor for High Country News. Email him at nickbowlin@hcn.org or submit a letter to the editor.