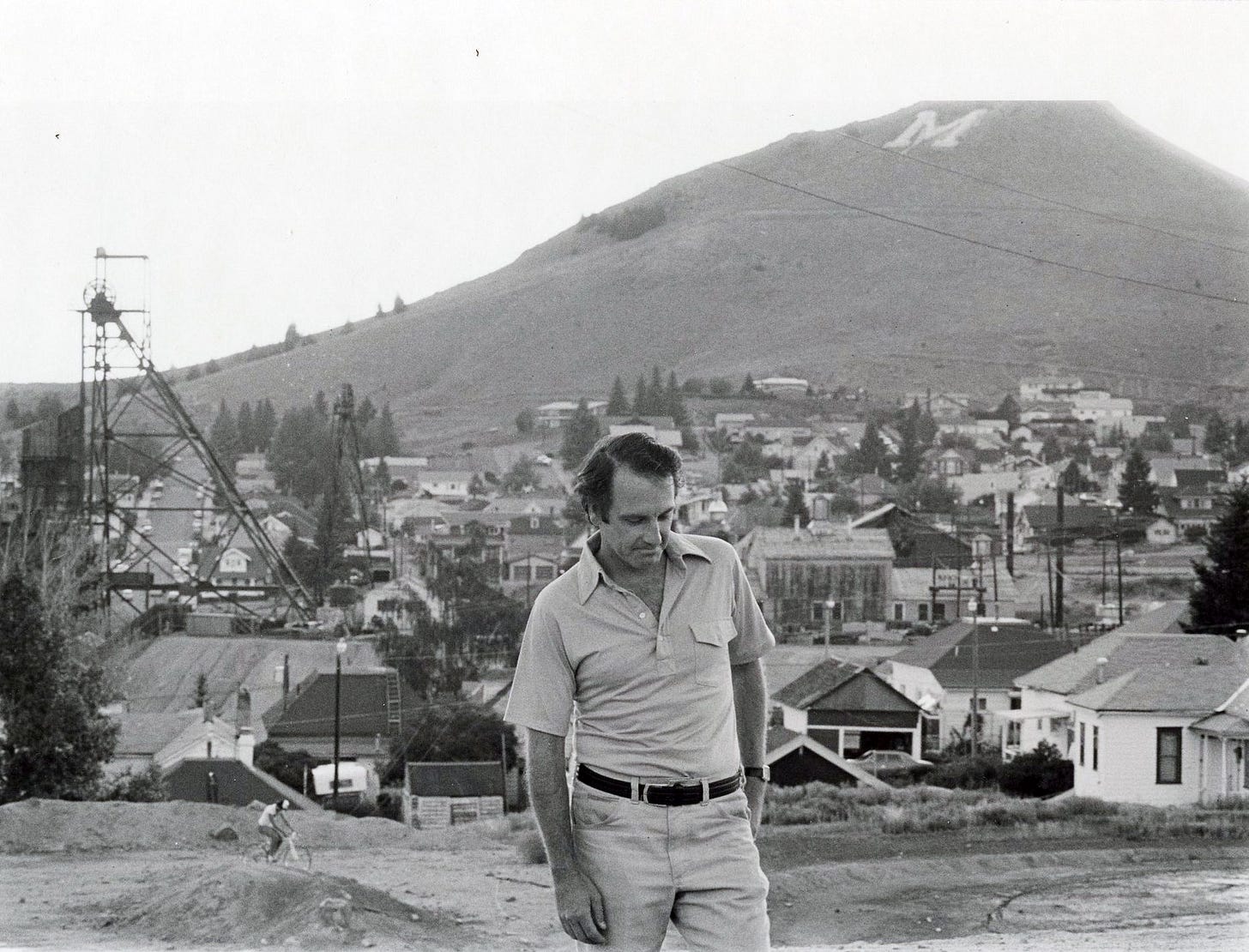

Pat Williams, Montana’s longest-serving U.S. House member, dies at 87

Williams, who was born and raised in Butte, served nine terms in the House

By Tom Lutey, Montana Free Press

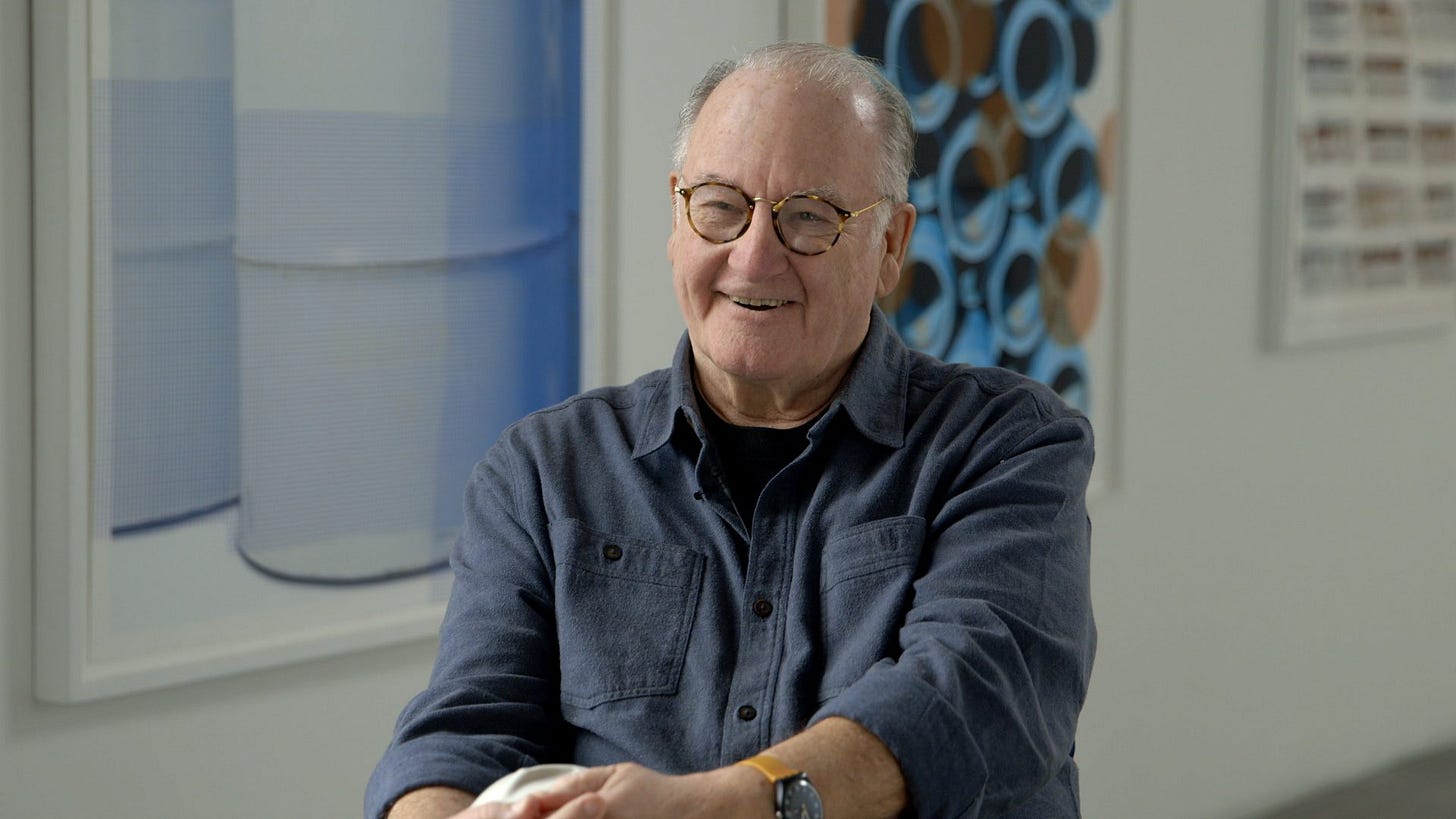

Pat Williams, Montana’s longest-serving member of the U.S. House, died Wednesday evening in a Missoula hospital.

The Butte native, who was Montana’s last Democrat elected to the House to date, served nine terms from 1979 to 1997, including two as the state’s at-large representative. Williams was 87.

“He was a hard-nosed politician but he had such a soft center,” said Sheena Wilson, a friend who hired on to Williams’ staff in Washington, D.C. “He knew a lot of people were having a lot more difficult time than he was, and he appreciated their position, understood their position.”

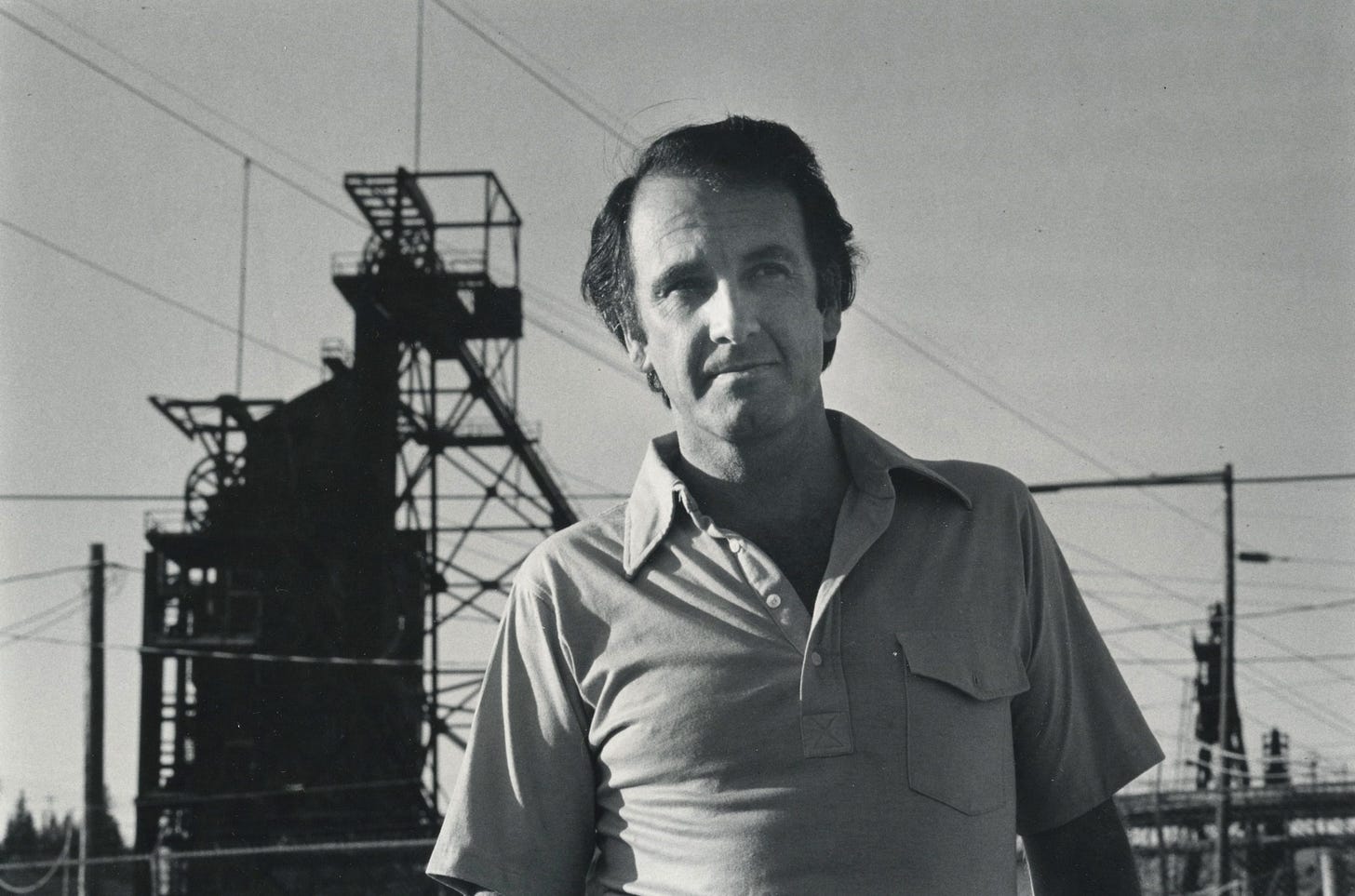

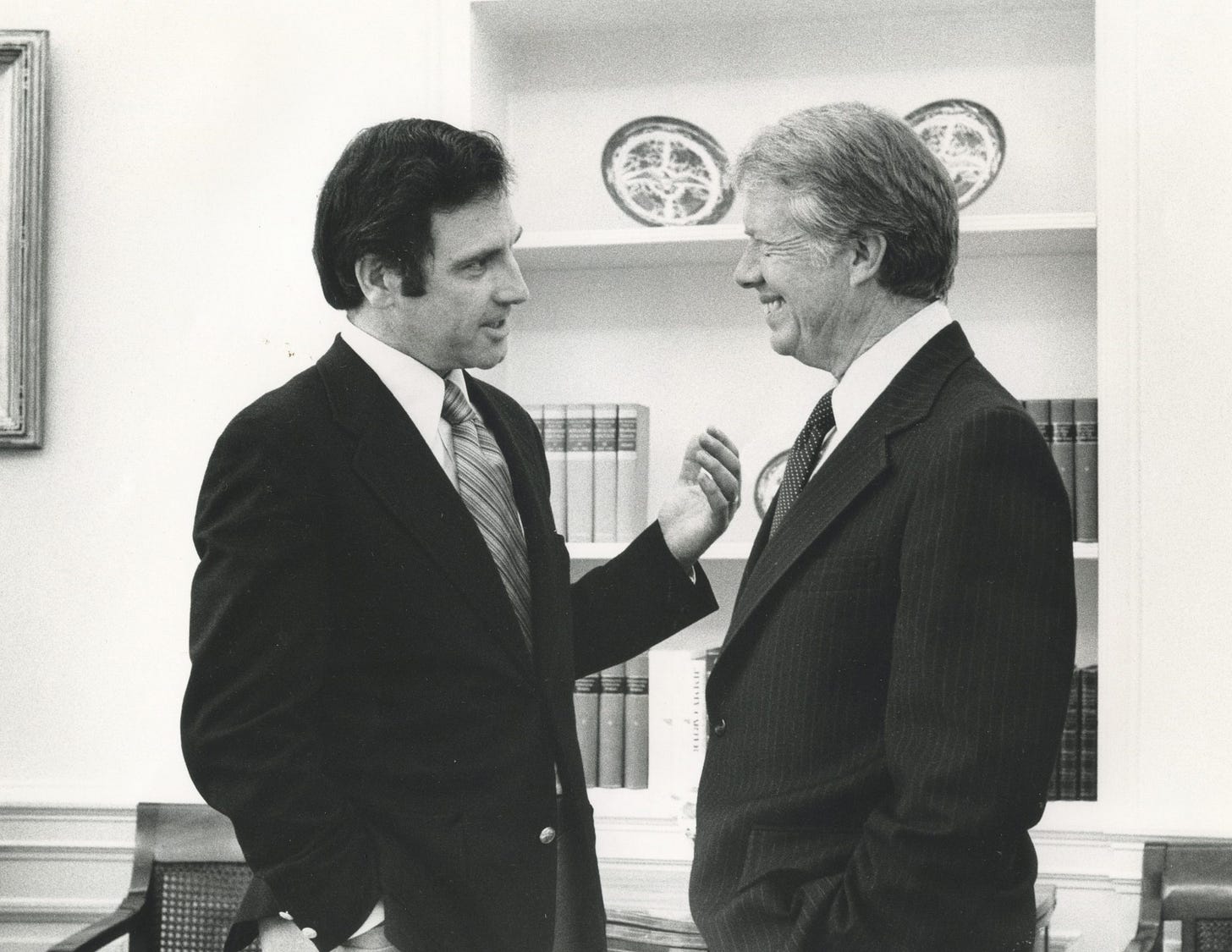

Photos Shared by the Williams Family

Williams was particularly proud of the 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act that assured workers up to 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected absence from work for the birth of a child, caring for a sick spouse, or adopting a child. Eight previous attempts under presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush had failed.

Williams, on the House floor speaking in support of the legislation, called the previous two administrations “frozen in the ice of their own indifference toward improving the working conditions, the safety conditions, the income/salary conditions of America’s middle- and lower-income workers.” His remarks appear in the Congressional Record for February 3, 1993.

The Montana Democrat’s willingness to speak critically of the executive branch while defending the powers of Congress would have made Williams an outlier in today’s politics, said Don Judge, a long-time friend and early supporter.

“He wouldn’t sit idly by when things were going south. He would disagree,” Judge said in an interview Wednesday. “I don’t think that’s a fish out of water, that’s a shark circling.”

Judge was an early believer in Williams, who first ran for the U.S. House in 1974 after working on the staff of then-eastern Montana Democratic Representative John Melcher. Williams lost the race to an up-and-comer from the Montana Legislature, Max Baucus, who would eventually become the state’s longest-serving U.S. senator.

Judge was leading the Montana AFL-CIO from an office in Helena, just a few doors down from Willams’ office. Consoling his friend about the Democratic primary loss, Judge offered Williams $5, promising to do the same every paycheck if Williams ran for the U.S. House again.

Williams did run again, and Montana’s western U.S. House District delivered a string of lopsided wins — he finished with less than 60% of the district’s general election vote only once. Friends said political opponents would accuse Williams of being anti-family, though he was sometimes the only candidate with children, two daughters and a son. His wife, Carol, and daughter Whitney had political careers of their own.

Opponents would question his patriotism, though Williams served in the Montana Guard.

The big election fight was in 1992, after Montana’s slow population growth, captured by the 1990 U.S. census, cost the state one of its two U.S. House seats. Williams and eastern Montana Republican Representative Ron Marlenee both filed for the state’s at-large district.

Williams won, but the race was tight, said Celinda Lake, a Democratic political strategist who counts Williams as one of her business’ first clients. Williams proved to be a blue-collar candidate who used polling properly, Lake said in an interview Wednesday, meaning he learned about voters, but didn’t reinvent himself to conform with survey results.

“He was always his authentic self,” Lake said. “He told me, ‘I want you to know my goals. I’m engaged in a 20-year conversation with the people of Montana about the benefits of good public education and the dangers of hard-rock mining.’ And I’ll never forget that.”

That conversation with the electorate began in 1966, the year Willams was elected to the Montana Legislature, representing Butte. After that he worked for Melcher.

Lake also said she won’t forget Williams’ concern for others. She briefly worked for Williams in Washington, D.C., before pursuing a new opportunity with the Women’s Campaign Fund, a political action committee formed to get more women elected to public office. Between jobs, she became seriously ill with a kidney condition and was without health insurance.

Unexpectedly, Williams called her up. “I’m putting you back on payroll,” he told Lake, meaning she could pay her medical bills.

The tilt with Marlenee in 1992 was challenging for Williams because he wasn’t seen very often in eastern district media markets. He had to at least run a close race in Yellowstone County, the state’s most populous, Lake said, while keeping conservative Flathead County from gravitating to Marlenee, a shrewd politician from the northeast Montana community of Scobey.

Williams won over eastern Montana farmers and ranchers with his populist message about banks. Banks from out of state were Montana’s largest lenders, Lake said, making loan competition limited. Farms were still recuperating from debt stemming from terrible economic conditions in the 1980s. Land values were low, which made collateralizing loans difficult.

The western Montana Democrat was also focused on increasing voter registration on American Indian reservations, said Joe Lamson, a former campaign manager and state director for Williams.

“Working with the tribes on voting rights, he was the first one to put real money on hiring organizers to get people registered,” Lamson said in an interview Wednesday.

Lamson said Williams was always a teacher in his approach. He worked as an educator before he was an elected official.

“He had faith in the inherent value of truth and his fellow citizens’ ability to understand it, and work together for our more perfect union, a long life we were all blessed to travel together.”

Williams took 51% of the vote in the 1992 election against Marlenee. He was reelected in 1994, but retired at the end of the term. The at-large district was brutal, Williams recounted in 2022, the year Montana became the first at-large state to regain a House seat. Running in a House district the size of the nation’s fourth-largest state was not unlike running in a Senate race every other year. House members get the same number of staff and the same number of district offices no matter how large an area they represent.