On MMIP Day of Awareness, Blackfeet Father Demands Justice

May 5 is a National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous People. As groups lead events nationwide, a Blackfeet father demands justice in his daughter’s case

By Nora Mabie, Montana Free Press

On the evening of December 28 last year, Chris Butterfly got a call that someone had been shot at his daughter’s boyfriend’s house.

Butterfly jumped in his car with his brother and called his 19-year-old daughter, Jadie Butterfly, as they drove. When she didn’t answer, he texted her.

“Please answer,” he thought. “Please say something else happened.”

When Butterfly arrived at the house in Browning, law enforcement officers told him Jadie was dead.

The rest, Butterfly said, was a blur. He stepped outside to call his wife.

“After I told her, I just heard screaming and crying in the background,” he said.

Jadie, an avid athlete and graduate of Browning High School, had been taking radiology courses at the University of Montana and planned to work in health care. She was a role model for her four siblings, her father said.

“She was our everything,” Butterfly said. “Our breath. Our future. Our light.”

Jadie’s death certificate lists a gunshot wound as the cause of death and identifies the manner of death as homicide. More than four months later, however, there have been no arrests or charges in her case.

Jadie, a citizen of the Blackfeet Nation, is one of thousands of Indigenous people who go missing or are murdered each year, a crisis so prevalent it has its own acronym, MMIP.

A state Department of Justice report found that Native Americans in Montana are four times more likely to be reported missing than their counterparts. And while Native Americans comprised 6.5% of Montana’s population in 2023, they accounted for 30.6% of reported missing persons that year.

May 5 is a National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Indigenous People. It’s also Hanna Harris’ birthday. A citizen of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe, Harris was killed in 2013 at age 21, leaving behind her 10-month-old son. Frustrated with law enforcement, Harris’ family, like hundreds of Indigenous families nationwide, fought for justice in her case. Harris’ mother Malinda Limberhand drove to nearby towns asking people whether they’d seen her daughter. She organized searches and obtained security camera footage from local businesses to understand her daughter’s whereabouts the night she went missing. Limberhand even drove a suspect to the police station for an interview.

In 2014, two people were charged in connection to Harris’ death. In 2017, Montana’s congressional delegation introduced a resolution designating Harris’ birthday as a National Day of Awareness. And in 2019, the Montana Legislature passed Hanna’s Act, authorizing the state Department of Justice to assist in missing persons cases.

While action in the wake of Harris’ death offered hope for change, more than 10 years later on this May 5, Jadie Butterfly’s family is still fighting for the same thing.

Tribal leaders and advocates say the MMIP crisis is a consequence of colonization and harmful U.S. policy. Federal laws — enacted over hundreds of years and in different political contexts — have created a complex patchwork of law enforcement jurisdiction on reservations. When a Native American goes missing or is killed, the investigative agency — whether state, tribal or federal law enforcement — is often determined by several factors including the severity of the crime, whether it occurred on or off tribal land and whether the perpetrator was Native or not.

Insufficient law enforcement funding, rurality and unequal media coverage, experts say, exacerbate the problem. A Columbia Journalism Review tool in 2023 estimated that a missing white woman in her early 20s would be the subject of at least 120 news articles, while a missing Native American woman of the same age in Montana would receive about 35 stories.

The complicated system is difficult to navigate, and Native families say systemic failures often stall justice. While the state and federal governments have enacted legislation to address the issue, advocates say more action is needed.

JADIE BUTTERFLY

The FBI, Glacier County, Blackfeet Law Enforcement Services and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives are investigating Butterfly’s death, according to the FBI.

While Chris Butterfly receives occasional updates from the FBI, he said the information is usually surface-level, as agency officials tell him they cannot disclose anything beyond top-level details about an ongoing case.

In an April 7 letter to the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council, Butterfly urged action from tribal police.

“We have received nothing but silence — no callbacks, updates or other communications,” he wrote of tribal police. “… I do not want my daughter’s case to slip through the cracks, as so many others have.”

Butterfly met with tribal police about one week after sending the letter but said he didn’t get meaningful answers from the agency. Blackfeet Law Enforcement Services Chief Misty Keller did not respond to several requests for comment from Montana Free Press.

Butterfly’s frustration with law enforcement isn’t uncommon in MMIP cases. While the federal government has a treaty responsibility to fund law enforcement services on most reservations, tribal leaders have argued for years that the money doesn’t come close to meeting community needs.

On the 1.5 million acre Blackfeet Reservation, which has a land size bigger than the state of Delaware, it’s common for just two tribal law enforcement officers to be patrolling on a shift. It can take hours for officers to respond to a call. The tribal court system, also chronically underfunded, is also understaffed and overwhelmed. As of last fall, the Blackfeet Tribal Court had one prosecutor. To get through a backlog of criminal cases, court officials said the court would have to operate 365 consecutive days, holding 11 jury trials a day.

Without meaningful communication from law enforcement, Butterfly said he feels like Jadie’s case “is at a standstill.”

“I just want to know what happened that night,” he said.

STATE AND FEDERAL ACTION

Two pieces of federal legislation enacted in 2020 have offered hope for change. The Not Invisible Act requires the Interior secretary to appoint members to a Joint Commission on Reducing Violence Against Indians. And Savanna’s Act aims to improve coordination among state, tribal and federal law enforcement entities through outreach and data collection.

A 2021 Government Accountability Office report, however, revealed federal failures in implementing the legislation. The Interior secretary had not appointed members to the commission by the requisite deadline, and the Department of Justice did not plan to continue its data analysis efforts beyond November 2021.

Similar efforts have hit barriers on the state level, too. In 2023, Montana lawmakers passed legislation to establish a grant fund to support community-led searches for missing people. Five months after the legislation was supposed to take effect, however, the state Department of Justice had not established the grant program, citing staffing issues within Montana’s Missing Indigenous Persons Task Force as the reason for the delay. Almost exactly one year into the job, Montana’s Missing Indigenous Persons coordinator, who leads the task force, left the post.

This year, state lawmakers have advanced legislation to bolster the state’s Missing Indigenous Persons Task Force and to enhance human trafficking prevention efforts in schools. State lawmakers have also pushed to increase funding at the federal level, though appropriations for law enforcement in Indian Country are ultimately decided by the U.S. Congress.

Federal entities have also announced new initiatives to address the crisis. The U.S. Department of Justice in April said it was sending new resources to Indian Country to address unresolved violent crimes. Part of Operation Not Forgotten, the FBI will assign 60 personnel to support field offices nationwide, including the Salt Lake Division that covers Montana.

MAY 5 IN MONTANA

Angeline Cheek, community organizer and activist, is organizing one of many MMIP awareness events in Montana this week. She expects about 500 people to attend the walk and expert panel she’s planned on the Fort Peck Reservation.

“For me, [May 5] is a day to remember victims and to remember families,” she said. “It’s a day of encouragement, too. For families to continue on, to move forward and to still fight for justice.”

Cheryl Horn, a member of the state’s Missing Indigenous Persons Task Force, has been organizing MMIP efforts since 2020, when her 16-year-old niece Selena Not Afraid went missing and was found dead in Big Horn County.

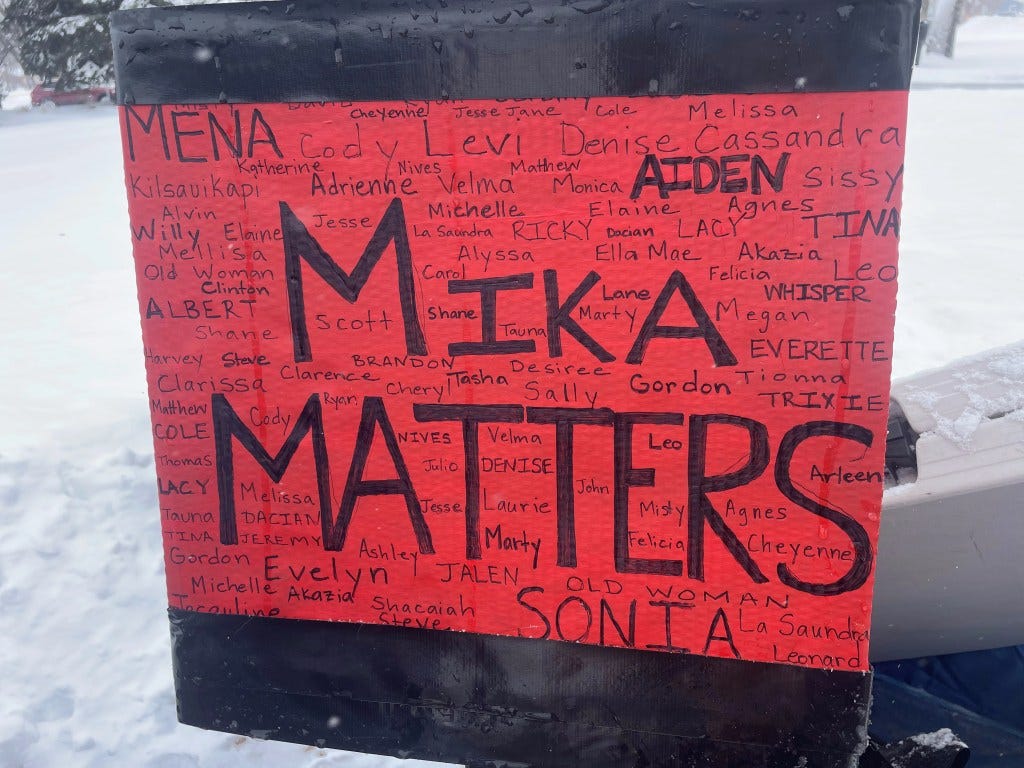

Preparing for a May 5 march on the Fort Belknap Reservation, Horn looked back at each of the vinyl posters she’d made for missing and murdered people in her community.

“I counted 18 signs,” she said. “I thought, ‘18 people in five years? On my little rez?’ I couldn’t believe it.”

For Horn, May 5 is “a day of hope.” In the five years she’s been advocating, she said she’s seen glimmers of change. In December, a man was charged in connection with Selena’s death. Last August, charges were filed in the case of Kaysera Stops Pretty Places, an 18-year-old woman who in 2019 was found dead just outside the Crow Reservation. And in February, a woman was sentenced to 10 years in prison for killing Mika Westwolf, a 22-year-old Native woman.

“What’s happening is people are getting their day in court,” Horn said. “In court, victims’ stories are heard in front of a judge and jury. That’s finally happening here. It’s sporadic, but it’s happening.”

On the Blackfeet Reservation, Butterfly is pushing for his daughter’s day in court. He created a “Justice for Jadie Butterfly” page on Facebook, where he encourages community members to share memories of Jadie, bring awareness to her case and demand law enforcement action.

“I’m advocating for her in every post I make,” he told Montana Free Press in a recent interview. “But every picture, every video just reopens up everything for me. It hurts. I just want justice so that we can have some sort of closure.”