Iowa State University Researchers Find Legal Deserts Across U.S.

By Brooklyn Draisey, Iowa Capital Dispatch

Small towns experiencing population decline often see staples like grocery stores, day cares and schools close, Iowa State University sociology professor David Peters said, leading to less access and hardship.

One less-known, missing part of many of these communities is legal representation, Peters said, which leaves people without recourse to handle problems of that nature or even the knowledge of when a lawyer is needed.

Peters, joined by two ISU students and future lawyers, conducted a study into lawyer shortages across the U.S. to identify where there is most need and go over practiced and possible solutions to ensure even those living in remote areas have access to the legal help they need.

“Not having enough lawyers puts rural people at a disadvantage because the legal system only really works if you have a lawyer that can either assert your rights or (provide) a mechanism to seek redress,” Peters said.

Emma Bartling graduated from ISU in the spring with a degree in agricultural and rural policy studies, and has enrolled in the University of South Dakota for law school with hopes of returning her home turf in Hardin County to practice. Emily Meyer still has one year of school left before graduation, but Bartling said both of them hope to return to rural areas to practice when they’re ready.

With this in mind, Bartling said she and Meyer got involved in the study to further their understanding of what they were getting into and why others weren’t following their path.

“To us, it was just an opportunity to better our learning and to kind of open a door that we would be going into, but just a little bit sooner,” Bartling said.

Peters was researching population decline in small towns when he came across the lack of private-practice attorneys, even in county seats where many residents go for their health care needs and other services they can’t find in their area.

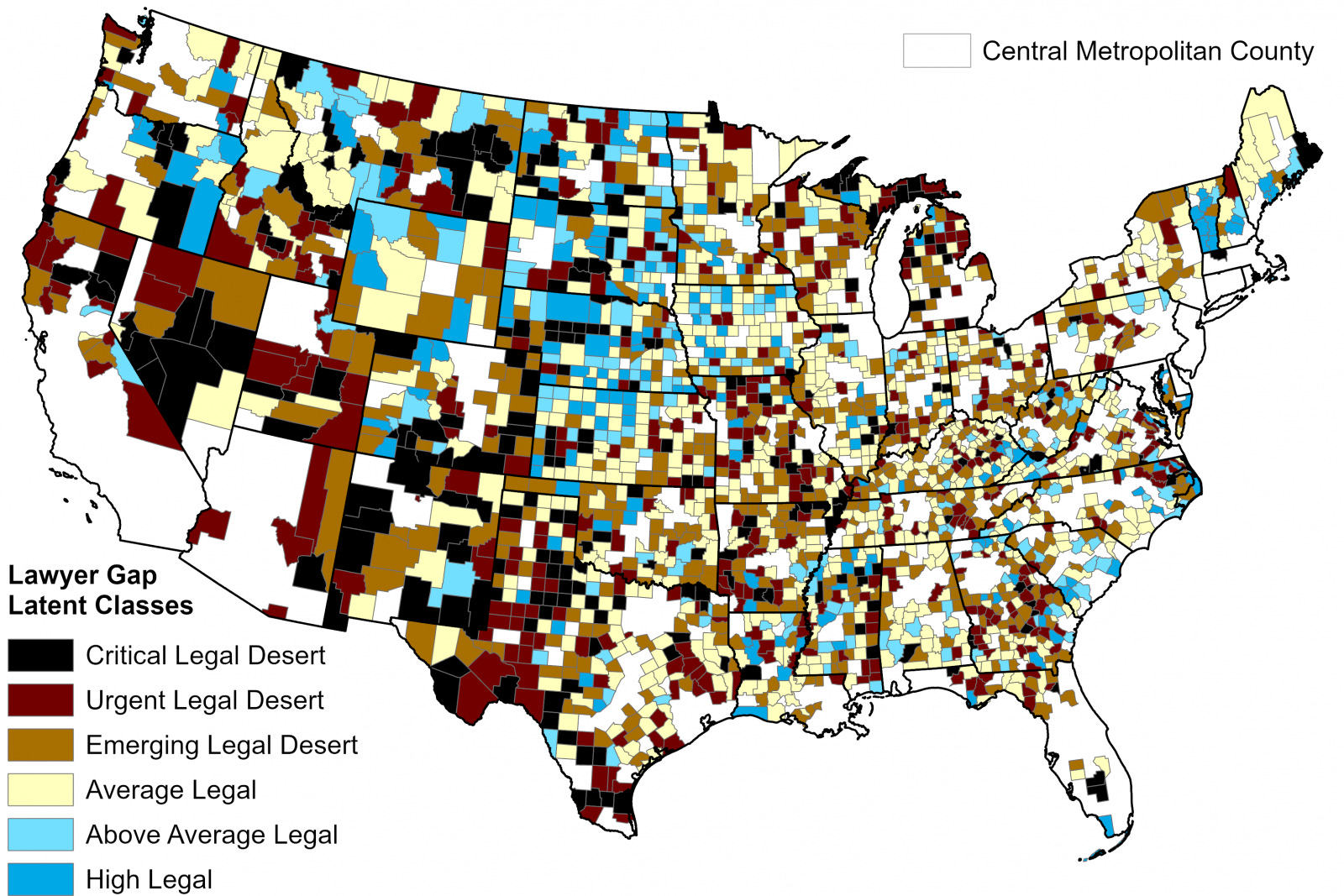

Rather than just looking at the total population of counties and comparing it to the number of lawyers practicing there, Peters said they used 2022 Census data to find out how many private-practice attorneys are located in each county and held it up to estimated demand for their services. These numbers helped determine if a legal desert exists in a given county and how severe it is.

Looking at more than 2,300 counties across the U.S., the study found that 11% of rural counties are critical legal deserts, with the largest gap between lawyer supply and demand for their services.

One example Peters gave was of Lee County — Iowa’s only county listed as a critical legal desert — where he said around 30 lawyers are practicing. Based on the county’s town populations, employers and other factors, the researchers found the county should have closer to 55 lawyers. Lee County is a “micropolitan county,” Peters said, as it has at least one town of between 10,000 and 50,000 people.

The majority of Iowa counties in the study were classified as having average levels of lawyers or higher, according to the study, with 10 counties identified as having emerging legal deserts. Most of these cases are in southern Iowa, Peters said, where farmland is less expensive and areas are more impoverished.

Bartling said that many counties with legal deserts are clustered together, so those looking for a lawyer might need to travel even farther. This could be especially scary and difficult to deal with for those experiencing domestic violence and the like.

“If those micropolitans, even, don’t have enough lawyers, then that just puts rural counties adjacent to that micropolitan (at an) even bigger disadvantage,” Peters said.

It surprised Peters to learn this, he said, and another shock came when the team learned pay for lawyers in rural areas was fairly similar no matter whether they were practicing in a legal desert or not, and the real pay gap is between urban and rural practices. This shows that using financial incentives to move lawyers into rural markets wouldn’t be very effective, he said.

Bartling and Meyer also looked into existing policy to try and solve this problem and identified their own solution.

Finding Solutions to Fill the Gap

Legal work is not the first thing people think of when they think of industry workforce shortages, Peters said, and in reality it is quite different from what is being experienced in the fields of health care and manufacturing, among others. There are surpluses of lawyers in some urban areas, and there is no federal push to address the issue.

South Dakota has seen success from a rural attorney recruitment program, Bartling said, which lets law students practice in rural counties before they have completed their schooling. The program has seen success, she said, but it won’t fit in every situation, just like other initiatives the team reviewed, like mobile legal clinics and external fellowship programs.

One program they identified as viable is a licensed legal paraprofessional program, Bartling said, where the state would allow those with legal training but not a full degree to practice independently in certain areas, like family law.

It would allow people from rural communities who have some legal training but another profession to fill a need without having to leave for years to get the highest licensure, and still be able to complete their other work when legal help isn’t needed, Peters said.

“I think it’s definitely up to states discretion how they want to implement it, but we saw that that would probably have the most impact, direct impact to the rural community members,” Bartling said.

Iowa Capital Dispatch is part of States Newsroom, the nation’s largest state-focused nonprofit news organization.